Writing Government Proposals: What Most Contractors Get Wrong

Aug 13, 2025When most contractors write a proposal for the U.S. government, they assume the executive summary is the golden ticket that shapes how evaluators see their bid. In reality, it often never gets read. Evaluation teams are typically split up, and each person reviews only their assigned section—ignoring the executive summary and everything outside their slice of responsibility.

That’s the first big takeaway from this lesson: every section of a government proposal must stand on its own. No cross-references. No hoping someone will connect the dots from other parts of the document. If an evaluator reads only your section, they should walk away with a complete, convincing case for awarding you the contract.

Drawing on his own experience as a Lieutenant supporting evaluation teams, Col. Louis Orndorff explains that evaluators operate under intense pressure—tight deadlines, large stacks of proposals, and little time for detective work. They don’t have the bandwidth to dig through other sections for context. The smarter move is to use the “Bottom Line Up Front” (BLUF) method in every section: start with the key point, promise, or benefit, then use the rest of the section to support it.

He recommends beginning each section with a short, direct summary that gives evaluators the big picture before they dive into the details. This mental framework helps them process your arguments faster and reduces the risk they’ll overlook something critical. It also makes your section easier to defend during review discussions—an important step in the decision-making process.

Not every section needs the same treatment. Some, like the contract responsibility determination, should be purely factual and concise. Others—especially technical narratives—require more care. These are often the highest-scoring areas in an evaluation, so they should be clear, well-structured, and easy for an evaluator to quote directly in their notes. In fact, the speaker points out that strong, well-written passages sometimes get lifted word-for-word into the evaluator’s justification.

This is why clarity matters. Dense, meandering text forces evaluators to search for meaning and risks losing their attention entirely. The more cognitive effort you demand from them, the more likely your section gets skimmed—or misunderstood.

The lesson here is that writing concisely is hard work, but it pays off. As the old Lincoln quote goes, “I would have written a shorter letter, but I didn’t have the time.” In proposal writing, trimming the fat and leading with the essentials isn’t just a courtesy—it’s a competitive advantage.

Key points from this approach:

-

Evaluators read only their assigned section—don’t depend on the executive summary.

-

Each section should be self-contained, with the BLUF method applied right at the top.

-

Respect the evaluator’s limited time and mental energy.

-

Keep factual sections short; make technical narratives clear, compelling, and quotable.

-

Strong writing can literally be copied into the evaluator’s notes, helping your case.

In short, the winning formula for government proposals isn’t hiding brilliance in the middle of a paragraph—it’s making brilliance unavoidable from the first sentence.

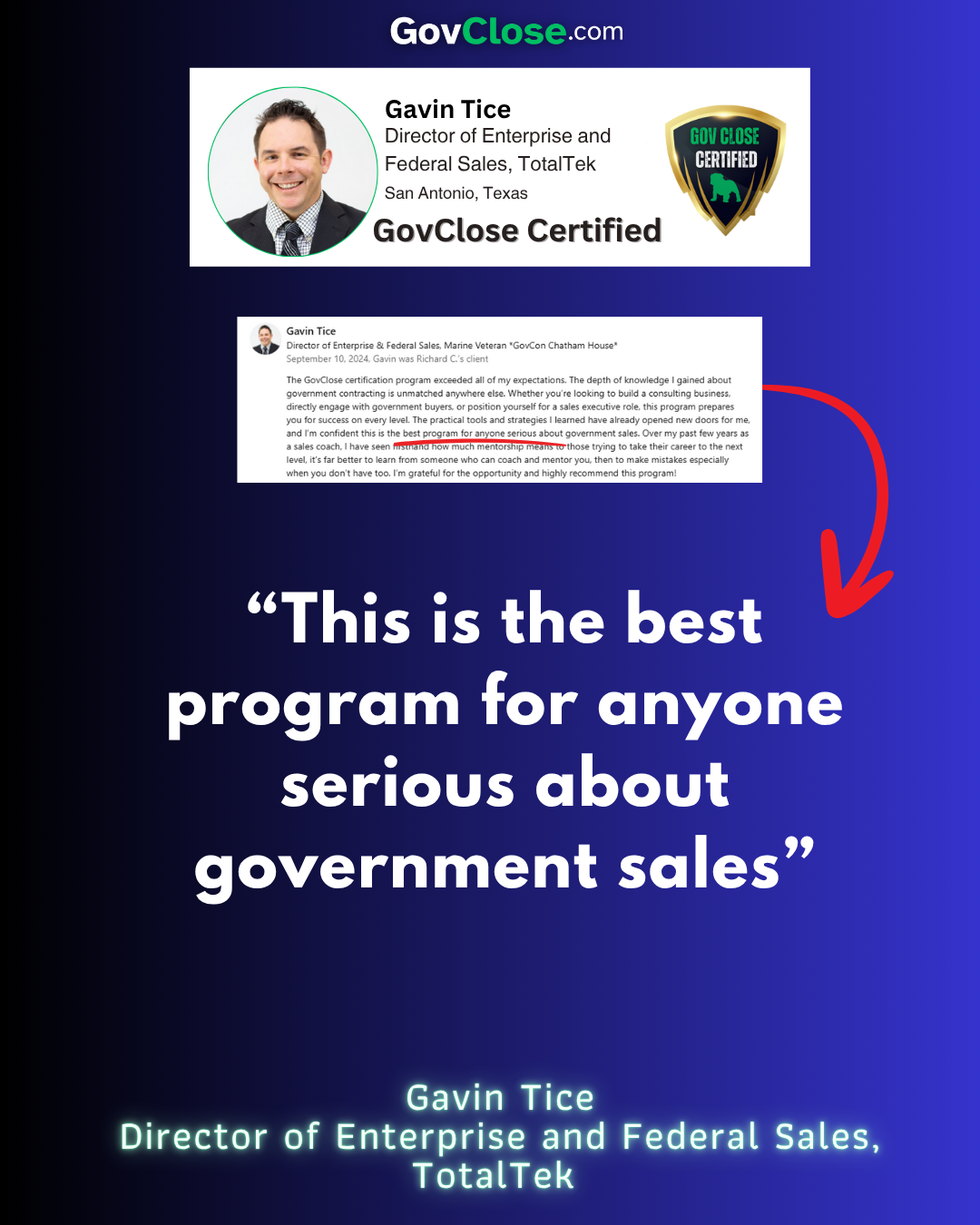

For those looking to start a consulting business in federal contracting, use their military or federal experience, sell to the government, or grow existing federal sales, more resources are available at GovClose.com.

Follow me on LinkedIn for free live training and GovCon updates: Richard C. Howard, Lt Col (Ret) | LinkedIn

Turn Government Contracting Knowledge Into Income

This isn’t a course. It’s a certification and implementation system to help you build a consulting business, land a high-paying sales role, or scale your own company in federal contracting.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.